What are Food Systems?

The term “food system” refers to all of the activities involved in producing, processing, transporting and consuming food. They are a crucial part in supporting nutritional health globally and have a huge effect on the health of our environment, economic systems, and livelihoods.

But too many of the world’s food systems are fragile, unexamined and vulnerable to collapse. In fact, recent crises such as COVID 19 or the war in Ukraine are exposing the fragility of our food systems with far-reaching consequences for the global food supply, leading to occasional (but increasingly frequent) sharp rises in food prices which have a devastating impact on the already most vulnerable.

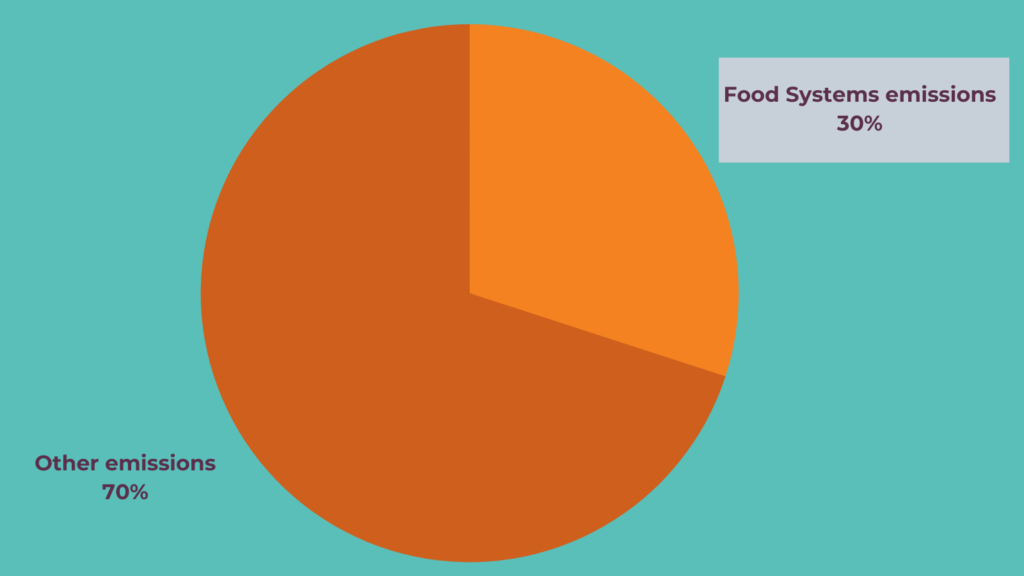

Food systems are also failing the planet, contributing directly and indirectly to global warming. It is now widely reported that food systems contribute an estimated 30% of total Greenhouse Gas emissions (GhG) and consumes 70% of all freshwater available for human use.

What are the current problems with our food systems?

Failing people:

Overall, poor diet is the leading risk factor for deaths in most countries in the world. The way the world produces and consumes food is leading to an unprecedented overweight and obesity epidemic, while failing to curb hunger. According to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) 2021 report, three billion people could not afford healthy diets before the COVID 19 pandemic hit.

Globally we produce more than enough food! But food is not getting to the people who need it most. Food production has increased between 300- to 400-fold since the 1950s. We have excess food in the system, but extraordinary inefficiencies in the way food is harvested, stored, processed, and transported is leading to 40% of all food produced being wasted (20% during processing and transport, another 10% at retail outlets, and another 10% by individual consumers). Meanwhile, 690m people are going hungry.

Failing the planet:

Food systems are the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, with more than 30% of total global emissions coming from food production.

The issue with livestock is the production of cattle feed, which drives deforestation (beef production drives deforestation five times more than any other sector) and water depletion (livestock raising accounts for half of the agricultural sector water use). It is estimated that altogether, the livestock sector is responsible for half of the global food systems emissions (deforestation + GhG biologically released by the animals).

Food systems are major contributors to biodiversity loss. The current agriculture system is dominated by only a few crop species with rice, wheat and maize providing half of the world’s plant-derived calories. The genetic diversity of livestock is also endangered: from several thousands in the 20th century, there are now only 500 pure-bred animals – which is eroding capacity for adaptation in the face of future challenges. Fish, which provide more than 4 billion people with an important source of protein and micronutrients, are not exempt from genetic erosion: overfishing is responsible for a third of fisheries to have collapsed.

A less biodiverse environment has multiple negative effects on people’s nutrition: it makes production systems more vulnerable to shocks, it reduces options for farmers’ income generation, and consumers have fewer dietary choices.

Monocultures are destroying natural habitats for other species and have devastating consequences for pollinators. In addition, they are particularly water demanding and often combined with heavy use of agrichemicals such as fertilizers and pesticides that pollute groundwaters, degrade soils qualities and affect natural carbon sequestration potential. This is contributing heavily to the decline in nutritional value of fruits, vegetables and grains that has been documented in recent years.

The climate change injustice:

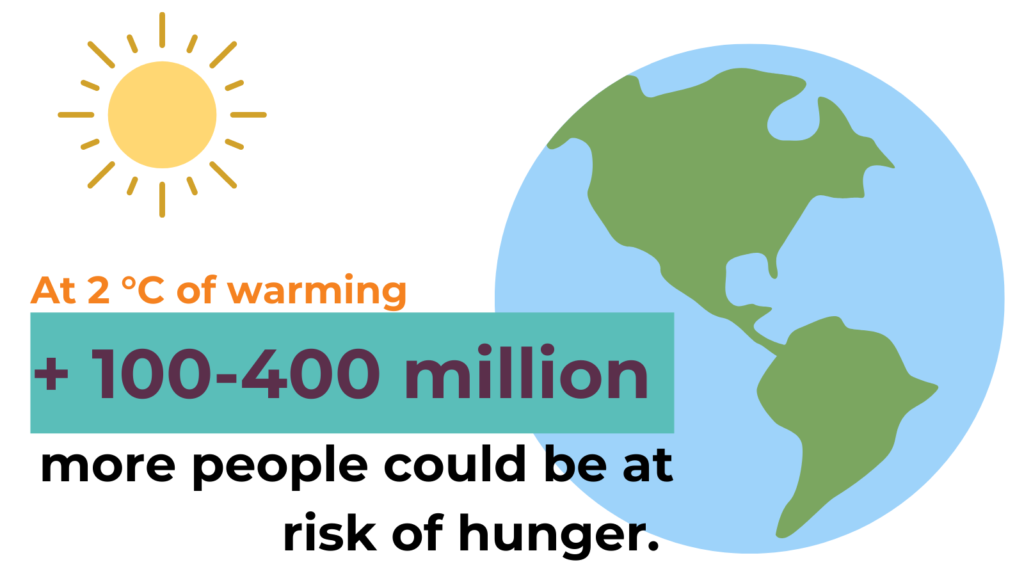

The impacts of climate change are affecting poor people and low-income countries disproportionately – although they contribute the least to climate change. There is growing scientific evidence suggesting that already water-scarce areas are becoming even drier and hotter. In West Africa’s Sahel region, for example, temperatures are rising 1.5 times faster than the global average. This is hitting many SUN countries where poverty, chronic malnutrition and sometimes conflicts are already tremendous challenges. According to the World Bank, at 2 °C degrees of warming, 100-400 million more people could be at risk of hunger and 1-2 billion more people may no longer have adequate water.

Food Sovereignty

Why food sovereignty matters? Today, decisions about what is produced, how it is produced, what is consumed and who has access to food are largely determined by multinational corporations and agribusinesses which control entire food chains and deploy immense lobbying efforts to influence governments and trade rules. In these tactics, hunger is sometimes instrumentalized to lift the ban on the use of GMOs or to push for the convergence of diets towards more imported and processed foods for example. Food sovereignty has grown as a countermovement to the growing dominance of industrial agricultural practices. It is defined as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems”. It is conceived as an alternative political framework and approach to food security.

What can we do about it as the CSN?

At global level:

Raise the visibility of the issues faced by SUN countries and amplify SUN stakeholder’s voices around climate change’s impact on nutrition security.

Advocate for a profound transformation of the global food system – from a model that favours the industrialised production of cheap commodities that are processed and shipped to developing countries, to a model based on agroecological production and local food systems that are geared towards providing for people’s nutritional needs.

Connect climate and nutrition activists (especially youth) and piggyback on the momentum that climate change will unfortunately continue to have in the decades to come in order to elevate nutrition as key to a sustainable healthier future for all.

Highlight the damaging impacts the global food system is having on the global climate crisis and how changing diets and food choices can drastically change that.

At country level:

At country level, if it is not the case already, encourage and support CSAs to connect the dots with FS pathways to ensure that nutrition features highly (balance between people and planet).

Encourage CSAs to consider biodiversity and soil’s replenishment as critical parts of nutrition-sensitive policies and advocate for food sovereignty approaches to food security.

Support CSAs to tap into climate mitigation and adaptation funding for the benefit of nutrition.